Blocking a newly discovered immune pathway enables microglia to control diffuse midline glioma, laying the groundwork for a future therapeutic strategy. Researchers have identified a powerful new way to fight diffuse midline glioma (DMG), one of the most aggressive and lethal pediatric brain tumors in preclinical laboratory models.

The findings, published today in Cancer Cell, come from a study led by Anne Rios (group leader at Oncode Institute and Princess Máxima Center) and colleagues and reveal a previously unrecognized immune mechanism with strong therapeutic potential.

By targeting a previously unrecognized communication pathway between tumor cells and brain-resident immune cells, the study demonstrates complete tumor control and long-term survival in preclinical models: a result not previously achieved in DMG immunotherapy research.

Children diagnosed with DMG have faced devastating odds. This rare brain tumor grows deep in the brainstem, an area that controls vital functions such as breathing and movement. Surgery is impossible, treatments are limited, and most children survive less than a year and a half after diagnosis.

A different kind of immune defense

Most cancer immunotherapies work by activating immune cells called T cells, which travel through the body to attack tumors. But the brain is different. It is a delicate organ, protected by strict barriers, and aggressive immune responses in the brain can cause serious harm. Instead of trying to force more immune cells into the brain, researchers began to look at the problem from another angle: What if the brain already contains the right immune cells, but their activity is somehow held in check?

Our path to this question was indirect. We first identified IGSF11, without knowing how central it would become. Only later did it become clear that targeting IGSF11 releases a brake on microglia, allowing the brain’s resident immune cells to act.

How the tumor disarms the brain

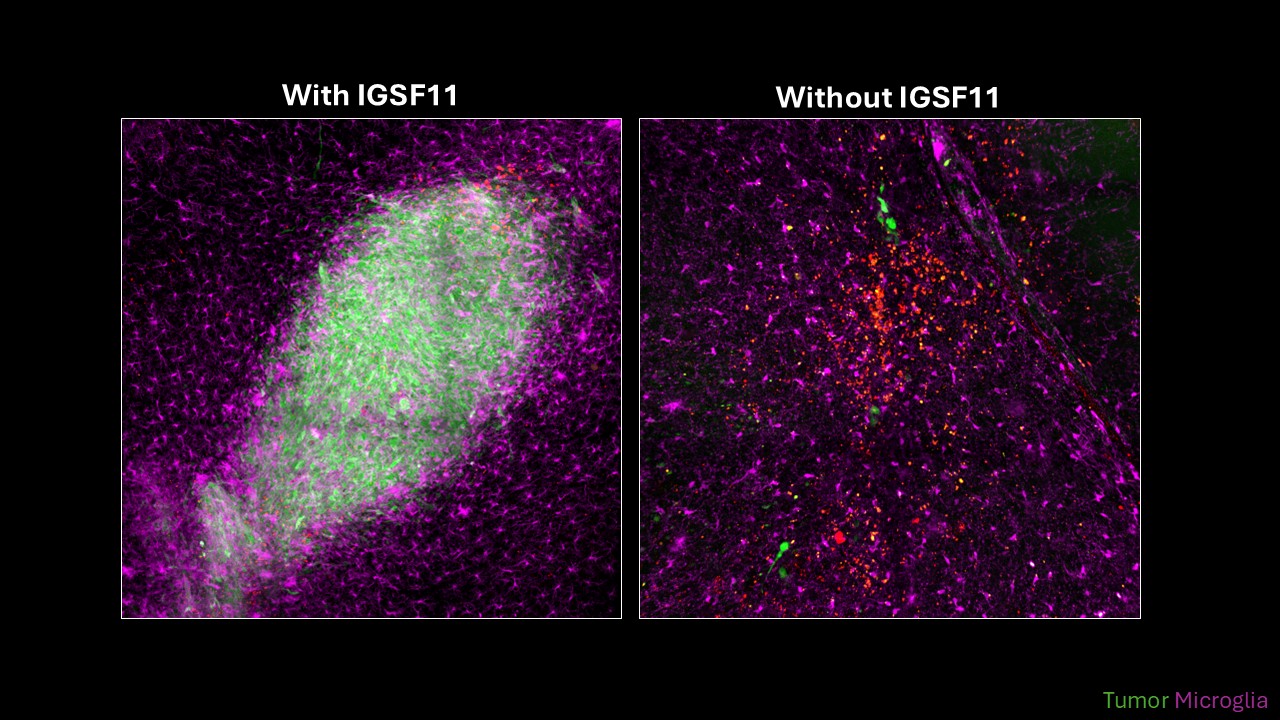

Studies of tumor samples from children with DMG showed that microglia do not recognize tumor cells as harmful. They do this through a molecular “handshake” involving two proteins: one on the tumor cell (called IGSF11) and one on the microglia (called VISTA). As long as this handshake exists, the microglia remain calm and the tumor is left alone. But when researchers blocked this interaction, everything changed.

Once the inhibitory signal was removed, microglia began to attack the tumor cells. In experimental models, this led to strong tumor control. In mice, the results were striking: all animals survived. Even more remarkable, this effect did not depend on T cells or other immune cells entering the brain. The tumor was controlled entirely by microglia, cells that were already there.

“Instead of bringing in outside immune cells, we allow the brain’s own immune system to respond,” says Rios. “That could be a much more natural and potentially safer way to treat brain tumors in children.”

This discovery opens the door to a new type of immunotherapy designed specifically for the brain. Because the target protein, IGSF11, is mainly found in brain tissue and is especially abundant in DMG tumor cells, treatments aimed at it may reduce the risk of damaging healthy organs.

The researchers are now working to translate this finding into a therapy by developing an antibody that can remove IGSF11 from tumor cells.

Anne Rios, senior author, Oncode Investigator at Oncode Institute and Princess Máxima Center for Pediatric Oncology

“This work shows that we don’t need to force the immune system into the brain to fight this tumor. By removing a single inhibitory signal, we allow microglia cells that are already perfectly adapted to the neural environment to do what they are meant to do. That opens the door to therapies that could be both highly effective and safer for children.”